We know that public health is a public good, but what exactly are we facing from a commons perspective with the current coronavirus outbreak in the world and Europe?

Consider for a while the question what the commons actually is, that we as Europeans, or rather as world community, are challenged to contribute to. We are requested to slow down the spread of the coronavirus to allow a better handling of the outbreak by the public health system. Concretely as a means to get there, we can view it as a public good in the form of a world with less private and business travel.

Thus, the social dilemma each individual scientist, activist, tourist or as a matter of fact any person faces is whether to cancel a big international conference, a workshop, a meeting, a private trip or say a long-term planned therapy. I have just read from a friend and IASC scholar who had to cancel an important project kick-off meeting saying “We do this although we know that there is nothing like in-person meetings for connecting”. The latter, by the way, is also an important insight from the commons theory. In order to slow down the spread we would need to avoid public transport, mass gatherings, festivals, concerts, conferences, meetings or any other crowded places. If we also want to protect more vulnerable groups, we would need to reduce number of visits to our elderly relatives and postpone visits to those who are already sick.

I have further read today some rather strong advice on the administrative homepage of my current region of residence in essence calling for more serious restrictions on my personal freedom: “Stay at home whenever possible and ventilate your rooms. Cut down personal contacts to a necessary minimum and use phone or social media instead. Cancel joint activities in associations, sport groups or private planned parties.” Sure, all of these are still less severe compared to staying in domestic quarantine, as thousands of Europeans are already forced to.

But what is the actual commons we are contributing to, summarizing all of this advice? The commons provided is a world with less and more careful personal interaction, in part through less travel no matter from far or near.

As this has all been very predictable over the last weeks, we might wonder which provision problem we face here. It reminds me in many respects of climate change as a social dilemma. Although, in contrast to the main obstacles to solve that dilemma, with the coronavirus the time span between action and feedback is much shorter and the likely outcomes are concrete and understandable. The risk is personal or with close people. But still, we can witness every day how difficult it is to engage in cutting down well-established habits and restricting the freedom of choice in order to contribute to the commons, in this case of global slowdown of the virus spread.

In the end, I hope that our commons theory background helps us to understand that by following some of these rules, we will contribute to the provision of a commons which makes us all better off! Strictly speaking, theory-wise this is no clear-cut case of commons-provision either, as my restricted behavior will also benefit me directly by reducing my own risks of getting infected, assuming that had not yet happened.

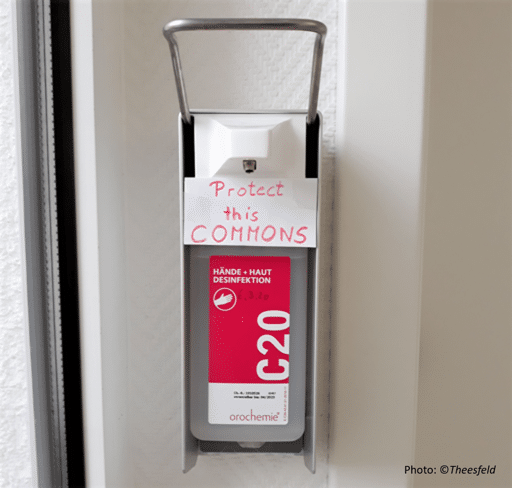

A close aspect I start wondering about is the provision of the commons in the form of ensuring that the disinfectant dispenser is in its place, exactly where the society most needs it. Hopefully, people do not need to read a coursebook on commons theory first to not steal and privatize such items.

Insa Theesfeld